If you have a curve, the gradient across the curve is constantly changing. The gradient at any point on that curve is called the derivative. The derivative tells you, essentially, the rate at which y is changing with respect to x. (There will be another post on infinitesimal calculus which will explain this further)

This process of differentiation is useful for understanding how many of the processes we see in nature work, particularly those in which the change is not necessarily constant.

An example of this is velocity, which you may have heard of as the derivative of position… but what does that mean?

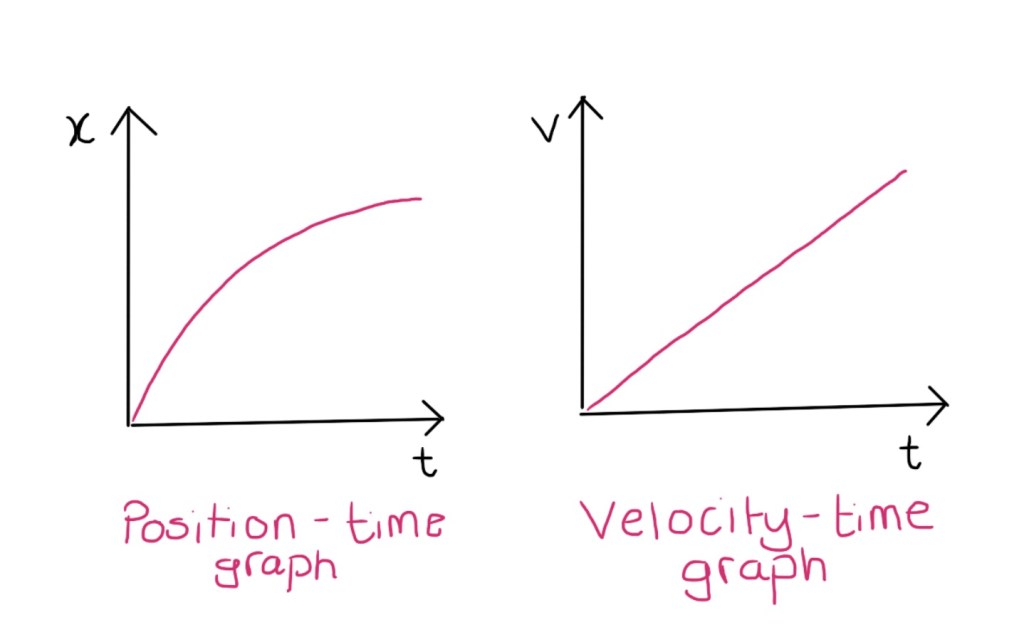

You can plot a graph of position (x) against time (t). If the graph is horizontal, the position is not changing over time. A diagonal or curved line indicates that the object is changing its position, and it is doing so with respect to time.

A straight diagonal line shows us that the object was covering a certain distance over a given time, and that it kept doing so at a constant rate. This is constant velocity: it stays the same and does not change.

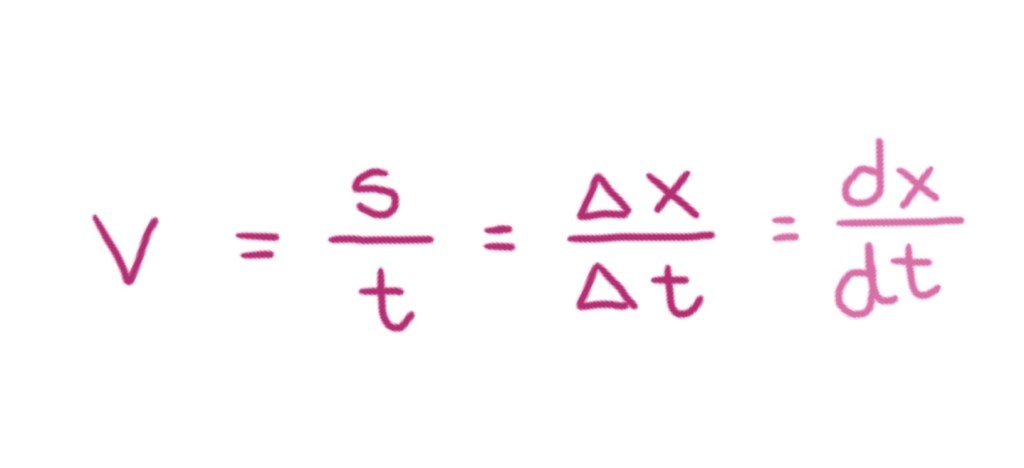

If we were to measure this velocity from the graph, we would use our equation for velocity: v=s/t, s being displacement (distance in a given direction). This means that we are measuring the change in position (the distance) in a given time, or:

Essentially, we are finding the gradient of the line.

Because this is a straight line, the gradient stays the same. But, if the line was curved, finding the gradient would be slightly more difficult. That is when we resort to our dear friend… the derivative (dx/dt).

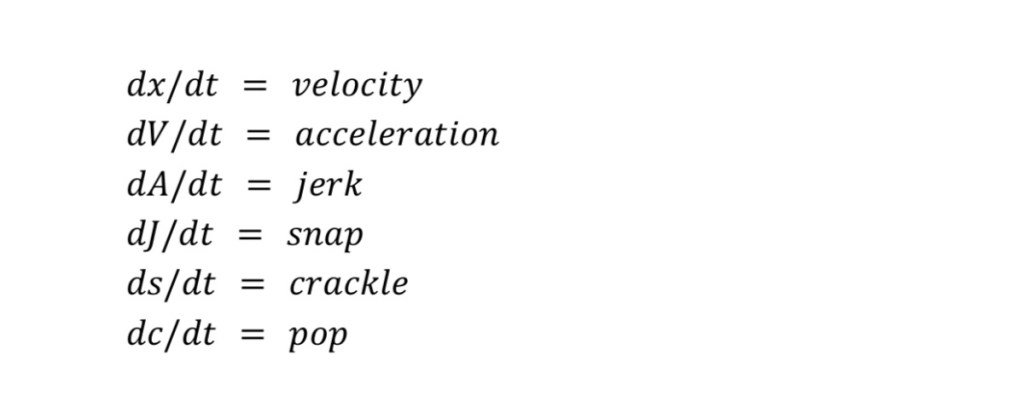

The derivative tells us the gradient of the line at any point, meaning in this case, it will tell us what the velocity is at every point on the curve. Which is why velocity is the derivative of position.

——————————————

What happens when you take the derivative of velocity? (In order words, the derivative of the derivative… the second derivative) Well, in order to think of this, we must draw a graph of velocity against time (instead of position against time). You can think of this as finding the gradient for every point along the curve of position against time, and plotting the gradients themselves.

If we took the gradient of the velocity-time graph, we would be calculating the change in velocity in a given time. In other words, we’d be calculating how much faster/slower the object is getting. This (you might have guessed it) is acceleration.

So the second derivative of position is acceleration.

——————————————

We can go on and on this way. The derivative of acceleration is how quickly/slowly the object is getting faster/slower, and it is called jerk. You can think of it by imagining yourself on a rollercoaster. If the rollercoaster speeds up gradually, it feels smoother than if it suddenly speeds up very quickly (where you would feel a jerk.)

Leave a comment